Unit 2: Critical Reflection

My critical reflection is centred around my making process and the artists and texts that have woven their way throughout the course of Unit 2. Personally, this unit has been very experimental and I have endeavoured to use the time to explore varied ways of illustrating my three central themes:

Aura and lingering presence within domestic objects and settings

Transitional objects and their effect

Ritual and superstition in relation to the body

Continuous oil pastel line drawings on Fabriano paper, 15 X 21 CM

I began the unit looking at Stone-Tape Theory and automatic writing. I explored working intuitively with the intention to engage on a subconscious level as I made tens of continuous line drawings whilst recounting memories.

Following this, I created a large series of small monoprints, utilising the same technique. The addition of drawing backwards and being unable to see the image until the eventual reveal, encouraged me to enact with greater fluidity. I proceeded to play with writing and realised that in writing backwards, I was able to partly subvert the habitual constraints around image making that I had previously manifested.

Continuous line drawing wood block mono prints on Ho-sho Japanese paper, 15 X 21 CM

Left to centre: Continuous line drawing on soft ground steel plate etching, printed on Somerset paper

Centre to right: screen etch resist on steel plate, etching with relief roll of Somerset paper.

I moved into etching but following my feedback from Unit 1 which included to attempt to move away from making resolved images, I realised I was still fulfilling this prophecy. Jo suggested that I contemplate the presence of the body within my work. This caused me to reflect, quite considerably, on my practice, why was I making the work that I was?

I considered why she said this and if I was able to see it myself. In Unit 1 I had been considering the lingering presence of those who have passed away within domestic settings and objects. My works were small, controlled, personal but not overly revealing, on the edge of vulnerability and most importantly, through the telling of the stories of others, I was indirectly trying to tell my own.

Left to centre left: soft ground etching plates for Filet exhibition

Centre right: soft ground etchings on Somerset paper, experimenting with display and incorporating the elephant.

Right: Soft ground etchings placed on top of my mum’s shirt pocket that I had removed, 7 X 10 cm.

One of my main points of reference within Unit 1 was the story of a couple, Margaret and Deryck Hudson, who I had known as non-biological grandparents. They had known my father since the 1960s and, after not being able to have their own children, had adopted the role of grandparents to myself and my sisters. Margaret had a lifetime of ill health and when she was in her early thirties tragically discovered that she had ovarian cancer and had to have a full hysterectomy. She was also in the early stages of pregnancy. After Deryck passed away in 2021 more than a decade after Margaret, I went through every photo album and desperately tried to recall the hundreds of stories he had told me over the years and relate them to the photos that began by depicting a young couple starting out on their married life in the 1940s full of hope for a happy future. The photographer, at times themselves or Deryck's mother, captures mundane domestic scenes in a celebratory fashion. These expensive and prized film photographs are of them washing dishes, helping each other to put on aprons and windowsills of low value but treasured belongings.

I felt an intense need to prolong and preserve their story but particularly her story, a woman who I had misunderstood when I had known her before she passed away in my teens. This is important because, it was only upon addressing Jo’s comment about the body that I realised that my infatuation with Margaret’s life was a way of deflecting from my own. Internally I was struggling to come to terms with my diagnosis of a chronic progressive health condition and the effects and limitations that it will have on the next stages of my life. It was through trying to understand Margaret’s story that I was trying to understand my own.

Threads taken from removing the buttons of my mother’s shirt.

In a subsequent moment of clarity, I became aware that what is significant within my practice, is the relationship between the body and the physical space that it exists in.

I was creating small, tentative artwork because as a person, I fear taking up space. My condition, Primary Lymphoedema, results in the progressive swelling of certain body parts as the result of a faulty lymphatic system. The treatment, to constantly compress the affected limbs, squashing and squeezing to make smaller. Therefore, I am acutely aware of the interactions between my body and the objects that hold me, touch me and surround me.

I put some big sheets of paper up on the wall, and, taking up as much space as I could, physically put myself in the space and allowed myself to spend time in the space that I was creating.

Oil pastel, chalk, acrylic paint, pen, pencil, relief ink, tissue paper, glue on Canaletto Paper, overall size approx. 200 X 172 cm

Tracey Emin has been a continued reference of mine throughout Unit 2. Her honesty and bravery that exists so strongly within her work has been a reassuring anchor as I have grappled with allowing vulnerability to enter my own making process. In the Radio Podcast, This Cultural Life, Tracey Emin says, “...there is a part of you that has to go deep inside, I sort of say inside the cave, and if you don’t go inside the cave you won’t be able to make any art.” (Emin, 2021) This was significant as I realised that in not going inside my own ‘cave’ that I was limiting myself and my practice.

A poignant reference has been the exhibition catalogue from her 2020-2021 exhibition Tracey Emin | Edvard Munch The Loneliness of the soul at the Royal Academy of Arts and her exhibition The Memory of Your Touch at Xavier Hufkins gallery.

Scanned images from Tracey Emin | Edvard Munch The Loneliness of the Soul (2020)

Left: Tracey Emin, I am The Last of my Kind, 2019

Centre left: Tracey Emin, Pelvis High, 2007

Centre right: Tracey Emin, Ruined, 2007

Right: Tracey Emin: You kept it coming, 2019

Frida Kahlo's paintings deal with the frailty of the body, life, birth and death. In Frida Kahlo and Tina Modotti, a White Chapel Exhibition catalogue from 1982, there is a chapter called “The Discourse of the Body.” The foundation of both their work was their bodies. It says, “Kahlo sought an iconic vocabulary which could both express and mask the reality of the body... a disregard for proportion and perspective...anatomical organs are often used as emblems.” Kahlo had a series of emblems and ornaments which she would use as symbols to explain the nature and effect of her condition. They are bold and unmistakable in their intentions to clearly illustrate her suffering.

Left: Henry Ford Hospital, Frida Kahlo (1932)

Right : A few Small Snips (1935)

The connotations of the emblem is something that Rebecca Solnit refences in her book, “The Faraway Nearby” a recommendation from visiting artist Katherine Jones. It is a memoir of Solnit’s experience of life just before and in the months following her Monther's death and her subsequent inheritance of three boxes of ripening apricots from her mother’s garden. The continuing decay of the fruit becomes a symbolic reminder of one’s own mortality. She relates her own emblem to vanitas that exist within art. She says;

“In paintings, vanitas often became a parade of particular emblems, including clocks and watches, hourglasses, musical instruments, candles burning down, skulls, bubbles and children blowing bubbles, and fruit and flowers that signified impending decay.” (Solnit, R. p.88 )

I considered my personal collection of symbols that are present within my practice. The chair, footstool, and bed are my emblems of hinting at my condition and decay. The apparently mundane objects are necessary ritualistic companions with superstitious energy that are part of my daily coping mechanisms.

Left: Monoprint on Canaletto 300 gsm paper, 100 X 70 CM

Centre Left: Drawn photo litho plate and the subsequent print on the off set press

Centre right: Monoprint on cotton with additional sewn parts, 100 X 70 CM

Right: A grouping of layered prints on paper and prints on fabric

At the start of the Unit, I visited the Freud Museum and took influence from two key elements. One, the underlying presence of energy within the space, the other, Freud’s compelling relationship with his antiquities. As well as using them as tools in his psychoanalysis, at times, Freud would refer to them as his “friends”. In chapter 6 of Perspectives on Contemporary Print Making, Clare Humphries essay Titled, Benjamin’s Blindspot: Aura and Reproduction in the Post-Print Age, she discusses the idea of the potency of objects that have been passed down from a deceased family member and whether the aura can be carried in the duplicate. (Humphries, 2015) It is quite common within our culture to recreate items that we believe have an aura of supposed luck.

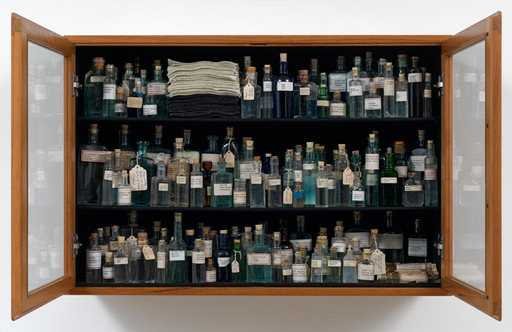

I was reminded again of the links between Josef Beuys and Susan Hiller and their significance to my practice. Josef Beuys with his “...strategy of charging ordinary materials with the aura of the relic (the artist as supreme choice-maker, the vitrine as warrantor of sacrosanct value).” (Hiller, 2021 p.136) And Susan Hiller with her collection of bottles of Holy Water, which demonstrate the “...viewer’s willingness to invest belief... believers want to trust that the souvenir vials they buy at pilgrimage sites are not just filled with ordinary tap water.” (Hiller, 2011. P.135)

Left: Homage to Joseph Beuys, Susan Hiller (1969–2011)

Right: Untitled (Vitrine), Josef Beuys (1983)

I had been carrying around a small elephant with me. I had referenced it in a collection of earlier etchings that I created for the Forces of the Small exhibition at Filet Gallery, the importance of the trunk facing the door for good luck. This was a stipulation for how my piece was exhibited. However, this superstition is a family one, as upon further research I have learnt that in fact you should face elephant away from the front door so that its positive energy flows into the home and not out through the front door! I gained enjoyment from the ironic fortune of interpreting one minute element incorrectly, it is possible induce the opposite of one's intention. I believe this speaks of the fragile nature of life and the desperation in hoping that superstition might change the course of a person's existence. This exhibition was a constructive learning experience, however the nature of it, being small, fed into my narrative of being afraid to take up space.

I decided to make a cast of the object to make duplicates. Clare Humphries talks about the aura of objects being passed down in replication. As I was casting the duplicates, still carrying the original elephant around with me, I realised that this was a ritual that I have performed throughout my life. I have written in my studio diary:

“I realised that I was caring for the object in my pocket in the way that I wished I could care for myself.”

I visited the Foundling Museum and experience that I reflect upon in depth in my Course Contexts, as it was pivotal in establishing the connection between myself and the small objects that exist within my practice.

Left: The start of making the plaster mould for my elephant

Centre left: A cast elephant before firing

Centre right: Three elephants painted with underglaze

Right: Collection of glazed and unglazed ceramic pieces on the studio windowsill

The notion of the “Transitional Object” was brought to my attention by a fellow student and again more recently by Fay Ballard. It is a term created by Donald Winnicott (1946-1951) to describe an item that can be used to provide psychological comfort primarily in unusual or unique situations. For example, a blanket or soft toy will often be the first item a child might associate with. These transitional connections allow the child to connect with the outside world beyond the maternal bond. However, the term is also relevant when referencing objects that we use to forge a connection to our surroundings in adulthood.

My feedback during the silent crits following the Bargehouse exhibition was fairly positive, and it felt apparent that my peers were picking up on the themes within my work. However, I was aware that I was still trying to present a comprehensive unity to my work, therefore eliminating the uncomfortable ambiguity that I had initially intended. The tension existed with the work but was ultimately tentative, still unable to allow complete vulnerability. After the exhibition I also realised that each piece does not exist in isolation and that they are in conversation with each other, with objects, smaller drawings, textures and sounds. I was questioning my decision to show them as individual pieces. This is something that is significant as I begin to consider what I will exhibit in the degree show.

Left: At Bargehouse Gallery, Throw Salt Over Your Shoulder (2023) 150 X 110 CM. Mixed media on paper.

Centre left: At Bargehouse Gallery, Pocket Pieces (2023) 100 X 70 CM. Mixed media on paper.

Centre Right: A selection of A5 continuous line drawings, reworked with paint

Right: A studio picture, showing the importance of surrounding information

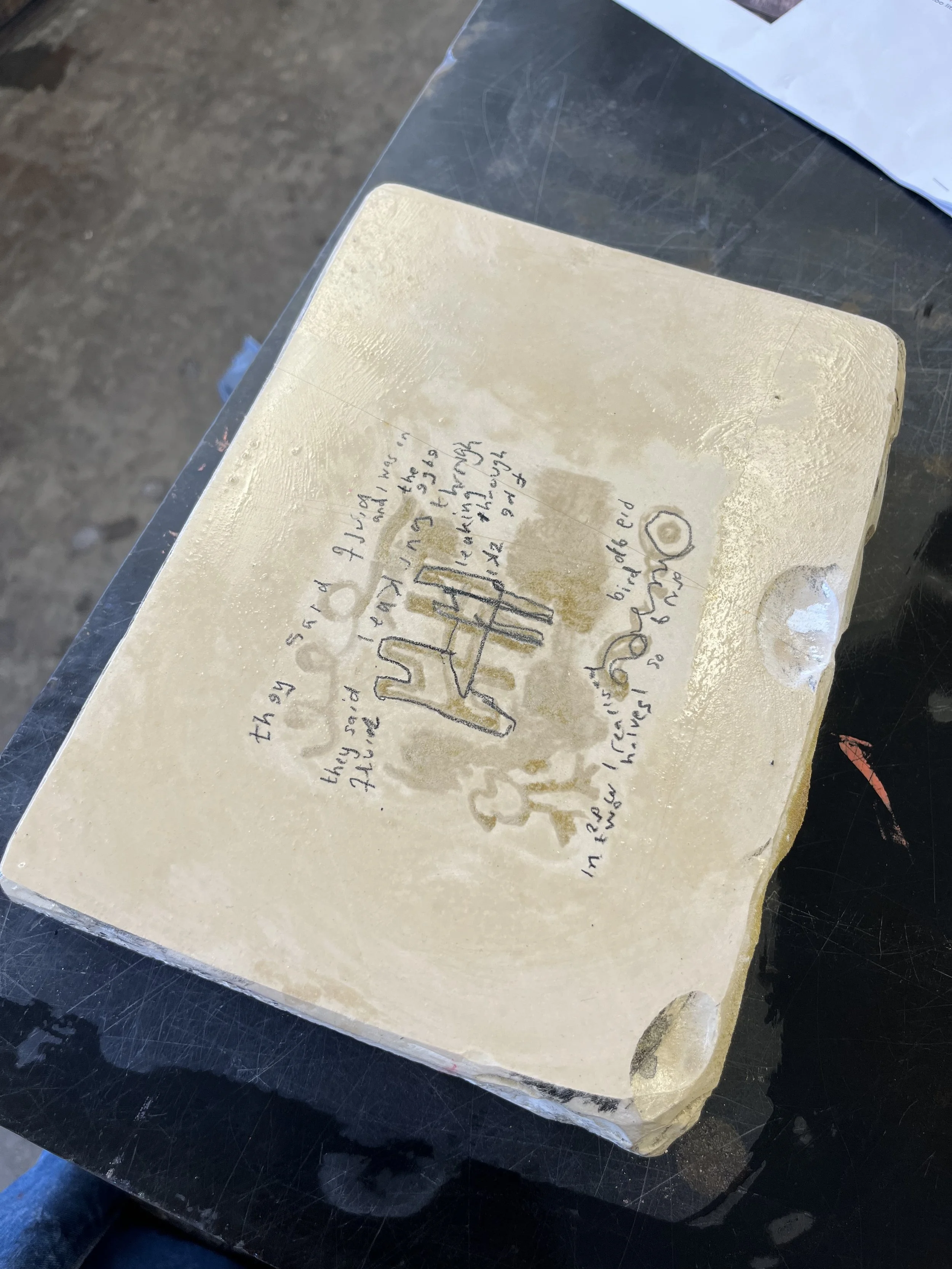

My work has become an amalgamation of monoprints, on fabric and paper, small ceramic objects and large scale drawings, torn up, rearranged and drawn over. I am drawing and layering, adding to and removing. My thoughts surfacing and then being covered and forced back down. They layering of tissue, paint and collage hinting towards the potential chaos submerged within. I am finding benefit when introducing photographic elements, moments of reality linking the more automatic marks to the real world. Over the past few weeks and upon reflecting over this Units’ works I have garnered some quieter moments within my work, with an emphasis on working intuitively, being present whilst making and increasing my focus on the body. I have begun drawing on litho stones using moisturising body products. I am interested to see how they progress and how they might sit with some of my other works as I go on to establish the small body of work that I wish to exhibit in the Degree Show.

Experimental works in progress, photographed in the studio.

Monoprints on cotton, printed on used photo litho plates using the off set press

Top Row: Monoprints on zerkall paper, 77 X 53 cm.

Bottom row: Monoprints of zerkall paper, 77 X 53 cm

Bottom right: Litho stone with drawing done in vaseline.