Unit 3: Critical Reflection

Critical Reflection

INTRODUCTION

Unit 3 has been transformative in the development of my practice visually and thematically. The most significant progression has been during the initial making process where I moved away from creating work with the intention of fulfilling a predetermined image. During the past unit I have challenged my approach to mark making and in using my body as a tool, my work has become more gestural and expressive, capturing a perceivable record of movement enabling the body to determine the final piece. This has allowed greater experimentation within my practice and has enabled me to develop a greater understanding of my key themes and where I wish to position my work.

At the start of each course Unit, we were encouraged to define our three key research areas. Gradually I have edged away from the object with a greater focus on the body. This has opened the possibility of inserting myself more fully into my work. I now consider the foundation of my practice as an exploration of how our physical bodies experience the world around us and personally, how I navigate it whilst living with a chronic health condition.

Throughout this piece of Critical Reflection, I will explore and provide evidence on how my key research areas, the body, physicality, and traces have shaped and informed my practice. More specifically, I will examine these themes in relation to my piece, And I went out the same door that I came in and in the context of ‘Bodies’ a book by psychotherapist and writer Susie Orbach and a selection of works exhibited at Sarah Lucas’ current exhibition ‘Happy Gas’ at Tate Britain.

Images left to right:

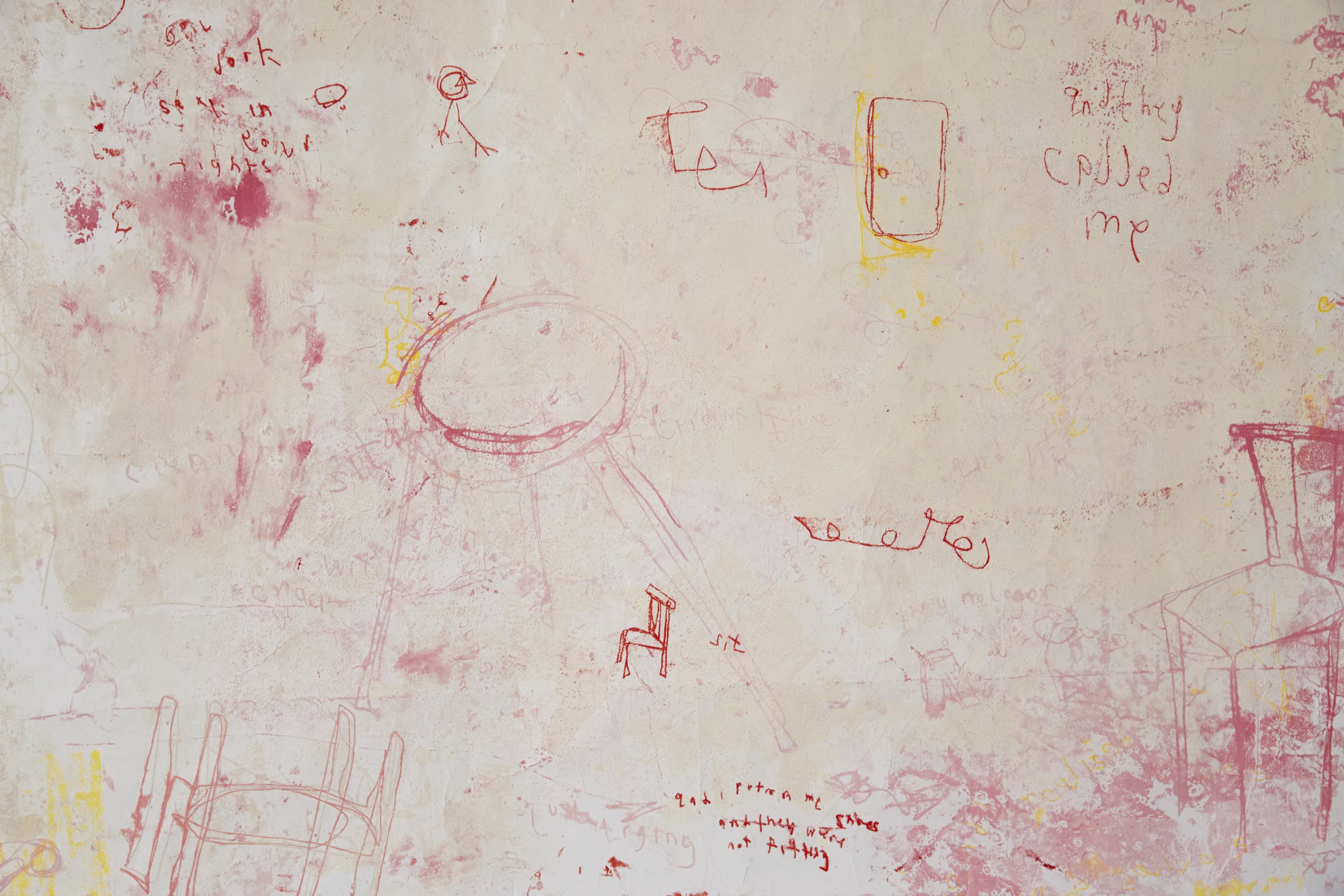

And I went out the same door that I came in, Joy Stokes (2023)

Eames Chair, Sarah Lucas (2015) Personal image taken at Happy Gas, Tate Britain

And I went out the same door that I came in, Joy Stokes (2023)

Me (Bar Stool), Sarah Lucas (2015) Personal image taken at Happy Gas, Tate Britain

THE BODY, PHYSICALITY AND TRACES

Within my practice I began to consider the ramifications of physically occupying space and the physicality of the human form existing within a room. I had been making small, tentative, and overly considered works that were reflective of my bodily preoccupation. I began to consider more specifically, the impact and significance of the body swelling and increasing in size. I started to question how we experience the size of our bodies; its concrete physicality verses our ideas of it.

Swelling can be a common bodily response to a range of factors, from injury to an underlying medical condition. It refers to the enlargement or puffiness that occurs when excess fluid accumulates in tissues. Primary Lymphoedema, a condition in which the lymphatic system fails to work properly, can cause chronic swelling in different body parts to varying levels of severity. The accumulation of this fluid causes visible swelling, accompanied by redness and tenderness. This swelling can cause intense discomfort and reduced mobility.

Physicality is a vital part of our actuality; it forms the basis of how we understand and create a tangible existence within the world. It is our physicality that is the medium or the vessel for which we can experience our surroundings and connect with others. Understanding our individual physicality is complex and varying. It can also be understood as a preoccupation with one’s body, which is a concept that I believe can be synonymous with having a health condition that affects the size of the body.

Throughout my life I have been encouraged to take up less space, a difficulty that I believe is mostly but not entirely symptomatic with being female. As a child, in contrast to my male counterparts, I was praised for being ‘little and cute’ rather than ‘big and strong.’ As a young teenage girl, I was repeatedly told, to ‘not grow up too quickly,’ which indirectly referred to stalling the process of puberty where naturally the body expands in size. It was the late 90s and early 2000s, more than a decade before the ‘Body Positivity Movement’ and the desired look was "Heroin-Chic", (The Guardian, 2022) endorsed by supermodels like Kate Moss and her well-known mantra “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.” (BBC News, 2018) I am intrigued in how evocative language can be in relation to the body and it’s size. Within my practice, I use writing as a means of storytelling and way or marking or recalling a moment in time. Often difficult to read or mirrored to provide protection from the outside world.

Language is an integral part of Sarah Lucas’ art, in her work, ‘Fat, Forty and Flab-ulous' (1990) a blown-up photocopy of an article from a now defunct British tabloid magazine, uncovers the misogyny and objectification towards women and their size. When experienced in the gallery, the language used in the article is incredibly confronting and objectively appalling. At the time, rhetoric of this nature was incredibly common in tabloid Newpapers and was a constant presence within established media. Although such articles and Newspapers face stronger scrutiny and are not published in the same way, the sentiment still very much exists. Despite being over thirty years later, it could be perceived as being as relevant as ever given the current climate of toxic masculine figures such as Andrew Tate. The abhorrent vernacular still forms part of the casual and everyday language within British culture, exacerbated by the anonymity of social media.

The body and it’s size is a complex issue. Psychotherapist Susie Orbach recognises how the Global North has become obsessed with size. She says; “Teenage girls in particular are so caught up in worries about their body size... They are a generation who have grown up with mothers who worry about the acceptability of their bodies and who they’ve seen be inconsistent, wary and often anxious about their own eating, size and body shape.” (Orbach, S. p.98-99) Here, she suggests that these anxieties are passed down through our mothers, who in their interactions with their daughters, are inherently transferring their own body anxieties to them. Orbach also highlights the ramifications of how women and girls perceive their bodies because of current external pressures and influences. (Orbach, S. p2) Therefore, we see a challenging combination of generational trauma and modern cultural pressures relating to physicality being transferred onto women.

As an adult, to be thinner or smaller, has been endorsed personally to me by medical professionals who applaud weight loss and reduction in the size of my limbs effected by Lymphoedema. This is alongside existing societal expectations and the reemergence of ideals from the 90’s which became increasingly apparent towards the end of 2022 when the New York Post published an article headlined, “Bye-bye booty: heroin chic is back” (New York Post, 2022). I realised that although deeply personal to me, exploring physicality and embodiment is a theme that is as important as ever and can be connected to by most and it was important to contextualise this within my practice.

I was able to first envisage how I could incorporate this into my work whilst recovering from an 8-hour car journey from London to North Wales. The temperature had reached 28 degrees and our car’s air conditioning had broken. My partner and I had gone to visit our family for the weekend, and I as the sole driver had driven us there. The result of driving for such a long time in excessive heat had huge repercussions on my body and physical health, due to the health condition that I live with. I felt frustrated and it was another reminder of the things that I am no longer able to do without negative bodily consequences. As I attempted to make myself physically smaller by reducing the swelling in my legs, it felt imperative that the artwork that I was going to make involved me taking up space and connecting to my limbs which are affected by lymphoedema.

Personally, I experience body disassociation from my affected limbs. It has become increasingly important to explore bodily unity and connection through my art practice. I wanted to learn more about body dysmorphia and feelings of being disconnected from the physical body. In ‘Bodies’ by Susie Orbach, one case study involves a man who feels so disconnected and hindered by his completely healthy legs that he wants to have them amputated.

“Such was the dilemma of Andrew, who became enamored with the idea of becoming free of at first one leg and then the other.” (Orbach, S p.15) Andrew is an example of extreme body dysmorphia, feeling so trapped and wrong within his body that despite having lived a fulfilling life for fifty years, he felt that only through a double amputation would he feel complete. The case study is subsequently unpacked and Orbach tries to understand the subject's contradictory emotional state of mind.

Nowadays, we have a more thorough understanding of adverse physical sensations such as a ‘phantom limb’ that is no longer there, as well as increased sensations in other body parts after amputation. This is because of the work of Dr Vilayanur Ramachandran; “Ramachandran showed that the patients he studied were not mad at all. Their brains had made a curious adaptation to the severing: the neural pathways of the now missing arms, legs or fingers were remapped onto other areas of the body.” (Orbach, S p17-18) However, in Andrew’s case, it was not that he was unable to feel his legs, his problem was that he perceived his legs so greatly that they made him feel incomplete and unable to have a sense of self-acceptance. Unable to find a surgeon willing to perform a medically unnecessary amputation and after many attempts at securing alternate forms of help, Andrew takes the matter into his own hands. “Eventually he inserted both his legs into a single support hose and then packed it with dry ice until he had cut off the circulation, so that a surgeon was forced to remove limbs which were atrophying.” (Orbach, S p19) Andrew, an able-bodied man had taken extreme measures to act upon his lifelong desire to reject his limbs.

In trying to understand what it was that led Andrew to spending fifty years discontented and disconnected to his lower body, Orbach looks back to his early years. She discovers that the consequence of a lonely, neglectful, and loveless childhood where Andrew would stare longingly out into an uneventful neighborhood would become the root cause of his struggles. The only exception to his otherwise solitary and mundane experience was the dreaded fear of being infected by polio. It was in the magazines he read as a child that suggested a life of living happily despite the effects of having contracted polio that showed a contrast to Andrew’s own lived experiences. This would lead him to wish that his body would stimulate a similar empathetic response and reflect his emotions.

“In his mind, Andrew grew a solution to his sense of being emotionally stranded: he would remake his body into one which aroused empathy – in others and in himself. He began to long for a body that exposed the wounds of feeling unlovable and unacceptable. A body that physically mirrored his emotional hurt and damaged. A body that might evoke some concern. As he approached adolescence, he secretly experimented with putting one leg into the trouser leg of the other and began to use crutches in a foreshadowing of the body he would have to wait almost forty years to obtain.” (Orbach, S p22-23)

We learn that due to his amputation, Andrew can find a sense of contentment and bodily fulfilment. Although an extreme example, this case study caused me to question my own struggles with body dissociation. I was also intrigued by Dr Vilayanur Ramachandran’s notion of feeling more increased sensations in other body parts after amputation. It has helped me to understand how I feel an increased sense of feeling in my limbs affected by Lymphoedema. I discovered that within my art practice, I am attempting to counterbalance my feelings of dissociation that I experience in part from my swelling and from the often out of body sensations, or feelings of observing my actions that I experience when performing my treatment measures.

This is where it became imperative that I use my body to create imagery through mark making. It is through traces and imprints made by bodily movement that I can see visual representation of my lived experiences. The Cambridge Dictionary defines the word ‘trace’ as “A sign that something has happened or existed”. (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023) Taking this idea, the marks left behind by my body on the paper are evidence of a moment in time. They are permanent fragments of otherwise transient moments.

Personally, the indelible marks that I make using my body through the lithography process or by monoprinting are a way of telling my story and I am always amazed at the visceral response I experience upon observing bodily remnants such as a mark that has been made by my leg or an imprint showing the texture of my skin.

I was able to first integrate traces and physicality fully into my practice when creating my main degree show piece And I went out the same door that I came in. I inked up a large wooden board and laid on top a sheet of Hosho paper. I took time to lie on the paper and to take up the entire space, using my body to apply pressure and create marks on the paper. I would then ink up the board again in a different colour and repeat the process again and on three separate sheets of paper. On one piece, I cut out the stencil of a chair and on the other a bed, to lay before the sheet of Hosho paper making ghostly silhouettes of objects that hold our bodies. The result, three multi-layered large monoprints, that in size were containers of my physical self and could be seen as a form of self-portraiture.

The choice of colour is important and I use it as a way of illustrating different intensities of movement. The softer, more bodily tones which can be seen as the basis of this work demonstrate slower and heavier movement that involves using the whole body. These large marks are in contrast to the small drawings and text that were overlayed on top as I subsequently worked into the paper. These more intricate marks are in deeper, more vibrant, and often neon colours. They can be likened to tattoos on skin or embroidery on fabric, penetrating the surface with concentrated areas of information.

The drawings are symbols and emblems, for example, the door representing the physical boundary between inside and outside, containing or releasing. A door being a barrier to the home is akin to the skin being seen as a barrier to one's body, containing that which is held inside from the outside world. The stool, the bed, the chair representing the objects that hold and support our bodies. Furthermore, it is possible to consider these household objects as representations of the human form.

As suggested by artist Sarah Lucas in the narrative pieces written throughout her current Tate exhibition Happy Gas, there is a symmetry between the human body and the furniture we sit on. She says; “We even call the parts of chairs arms and legs. It’s easy to imagine someone sitting in them... The person is already implied. With soft furnishings they also take on body shapes according to their fabric and stuffing, creating various creases and folds which can be suggestive.” (Lucas, S.) Within my work, I have always been drawn to certain pieces of furniture for this reason. I have pieces of furniture that specifically aid in my treatment, footstalls, reclining chairs, space big enough to hold myself and my pneumatic pumps. In the future, I am keen to explore bodily traces in relation to the marks made by the weight of the body on objects. For example, the impression left on a cushion by an elevated leg.

Having garnered a greater understanding of my practice and where I wish to position it, I came across an opportunity to exhibit in the ‘Bill of Health.’ This would be a group show at Central Saint Martins window galleries that coincides with UK Disability History Month, featuring 17 artists across UAL who have experience with chronic illness, disability or being a care giver. I was fortunate enough to have my work, And I went out the same door that I came in accepted to be a part of the show. It has been a fantastic opportunity to create connections with other artists who work within similar themes as well as placing the work in the context that I wish for it to be seen in. It has also enabled me to have a continued dialogue with Lucy Chapman, an artist and researcher in Art and Science.

Video stills: taken from my process video documentation for my piece: And I went out the same door that I came in

Moving Forward

The MA Fine Art: Printmaking course has enabled me to explore and develop my practice in a way that I could not have anticipated when I started the course. I have integrated my physical self fully into my work and have pushed myself thematically and materially. I would love to take this further, including experimentation with more sculptural works that push the ideas of bodily traces and physicality in a three-dimensional space. I have been incredibly fortunate to have been given the Lithography Fellowship and am looking forward to investigating and developing my skills further whilst also pushing traditional Lithographic techniques.

In reflection, I may have been able to push my ideas further, particularly in terms of display. I have found the use of neon paint particularly effective as used in my collaborative piece, Dialectics of the Skin. I would like to experiment using neon lights as a form of back lighting and feel this could have work well with And I went out the same door that I came in. It was also in this collaborative piece that I became enthused by the effective combination that print and the sculptural materials could create. In the future I wish to integrate more sculptural pieces within my own practice, expanding on mixed media works.

Throughout Unit 3 I have been preparing to take my professional practice outside of the academic setting. I have been actively making connections, applying to open calls and plan to continue along the trajectory that I have put myself on. With a greater sense of understanding, I am more confident in approaching other institutions and organisations that focus on themes of the body and health. I have also made huge changes in my personal life, including a new career path within the arts. My vocational pivot towards an Arts orientated industry as well as prioritising my physical health means that I will be able to actively engage in my practice with greater accessibility.

Word count: 3,099

Images left to right:

Detail of skin imprint from Zinc Lithograph print

Bill of Health, Central Saint Martins Window Gallery

Impression made by my leg on a cushion

Lithography stone

Bibliography

Ahrens, C & Smith K (1999) Kiki Smith: All Creatures Great and Small, New York, Scalo

BBC News (2018) Kate Moss regrets 'nothing tastes as good as skinny feels' comment. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-45522714 (Accessed: 6 November 2023)

Emin, T. (2017) The Memory of your Touch, Brussels, Xavier Hufkens

Foo, S (2023) What My Bones Know, London, Allen & Unwin

Hentschel, M & Seifermann, E (2008) Kiki Smith: Her Home, Berlin, Kerber Verlag

Lucas, S (2023) Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas, London, Tate Publishing

Lucas, S (2012) Sarah Lucas: Ordinary Things, Leeds, Henry More Institute

New York Post (2022) Bye-bye booty: Heroin chic is back. Available at: https://nypost.com/2022/11/02/heroin-chic-is-back-and-curvy-bodies-big-butts-are-out/. (Accessed: 6 November 2023)

Orbach, S (2009) Bodies, London, Profile Books LTD

Orbach, S (2016) In Therapy, London, Profile Books LTD

Walter, N (2010) Living Dolls, The Return of Sexism, London, Virago Press

Whiteread, R (2004) Rachel Whiteread, London, Tate Publishing

Van Der Kolk, B (2015) The Body Keeps the Score | Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma, London, Penguin Books

Exhibitions

Anslem Kiefer Finnegans Wake (2024) [Exhibition] The White Cube, London. 7 June – 20 August 2023

Dear Earth (2023) [Exhibition] The Hayward Gallery, London. 21 June – 3 September 2023

Philip Guston (2023) [Exhibition] Tate Modern, London. 5 October 2023 – 25 February 2024

Sarah Lucas Happy Gas (2023) [Exhibition] Tate Britain, London. 28 September 2023 – 14 January 2024

Milk (2023) [Exhibition] The Welcome Collection, London. 30 March 2023 – 10 September 2023

Podcasts

BBC Sounds (2023) Haunted Women [Podcast] 22 October 2020. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0009r62 (Accessed: 6 November 2023)

BBC Sounds (2023) This Cultural Life: Rachel Whiteread [Podcast] 6 February 2023. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001hws2 (Accessed: 6 November 2023)

Apple Podcasts (2023) The Great Women Artists: Kiki Smith [Podcast] DATE RELEASED Available at https://www.thegreatwomenartists.com/katy-hessel-podcast (Accessed: 6 November 2023)

BBC Sounds (2023) Witch [Podcast] 23 - 30 May 2023. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/brand/m001mc4p (Accessed: 6 November 2023)